Revitalizing Agricultural Research for Global Food Security

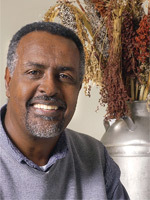

Gebisa Ejeta

Monday, 12 Oct 2009 at 8:00 pm – Sun Room, Memorial Union

Gebisa Ejeta of Ethiopia is the recipient of the 2009 World Food Prize for his work developing sorghum hybrids resistant to drought and the devastating Striga weed, or witchweed. The science has increased the production and availability of sorghum, one of the world's five principal grains and a staple in the diet of 500 million people living in sub-Saharan Africa. Ejeta was raised in a one-room thatched hut in rural Ethiopia and through education was able to rise out of poverty. It was during the 1980s while working in Sudan that he developed his first hybrid sorghum. He subsequently worked to integrate seed distribution with farmer education programs and conservation initiatives and to promote economic development in rural Africa. Ejeta earned his Ph.D. in plant breeding and genetics at Purdue University, where he later became a faculty member and today holds a distinguished professorship. The 2009 Norman Borlaug Lecture and part of the World Affairs Series.A reception and student poster display will precede the lecture from 7 to 8 p.m. in the South Ballroom, Memorial Union. Posters will address world food issues and are submitted by undergraduate and graduate students. The competition is funded by the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, the College of Human Sciences, and the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

2009 World Food Prize Laureate Gebisa Ejeta

The 2009 World Food Prize will be awarded to Dr. Gebisa Ejeta of Ethiopia, whose sorghum hybrids resistant to drought and the devastating Striga weed have dramatically increased the production and availability of one of the world's five principal grains and enhanced the food supply of hundreds of millions of people in sub-Saharan Africa.

OVERCOMING EARLY OBSTACLES THROUGH EDUCATION

Born in 1950, Gebisa Ejeta grew up in a one-room thatched hut with a mud floor, in a rural village in west-central Ethiopia. His mother's deep belief in education and her struggle to provide her son with access to local teachers and schools provided the young Ejeta with the means to rise out of poverty and hardship. His mother made arrangements for him to attend school in a neighboring town. Walking 20 kilometers every Sunday night to attend school during the week and then back home on Friday, he rapidly ascended through eight grades and passed the national exam qualifying him to enter high school.

Ejeta's high academic standing earned him financial assistance and entrance to the secondary-level Jimma Agricultural and Technical School, which had been established by Oklahoma State University under the U.S. government's Point Four Program. After graduating with distinction, Ejeta entered Alemaya College (also established by OSU and supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development) in eastern Ethiopia. He received his bachelor's degree in plant science in 1973.

In 1973, his college mentor introduced Ejeta to a renowned sorghum researcher, Dr. John Axtell of Purdue University, who invited him to assist in collecting sorghum species from around the country. Dr. Axtell was so impressed with Ejeta that he invited him to become his graduate student at Purdue University. This invitation came at a time when Ethiopia was about to enter a long period of political instability which would keep Ejeta from returning to his home country for nearly 25 years.

Ejeta entered Purdue in 1974, earning his Ph.D. in plant breeding and genetics. He later became a faculty member at Purdue, where today he holds a distinguished professorship.

Upon completing his graduate degree, Dr. Ejeta accepted a position as a sorghum researcher at the International Crop Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) office in Sudan. During his time at ICRISAT, Dr. Ejeta developed the first hybrid sorghum varieties for Africa, which were drought-tolerant and high-yielding.

With the local importance of sorghum in the human diet (made into breads, porridges, and beverages), and the vast potential of dryland agriculture in Sudan, Dr. Ejeta's drought-tolerant hybrids brought dramatic gains in crop productivity and also catalyzed the initiation of a commercial sorghum seed industry in Sudan.

His Hageen Dura-1, as the hybrid was named, was released in 1983 following field trials in which the hybrids out-yielded traditional sorghum varieties by 50 to 100 percent. Its superior grain qualities contributed to its rapid spread and wide acceptance by farmers, who found that yields increased to more than 150 percent greater than local sorghum, far surpassing the percentage gain in the trials.

Dr. Ejeta's dedication to helping poor farmers feed themselves and their families and rise out of poverty propelled his work in leveraging the gains of his hybrid breeding breakthrough. He urged the establishment of structures to monitor production, processing, certification, and marketing of hybrid seed and farmer-education programs in the use of fertilizers, soil and water conservation, and other supportive crop management practices.

By 1999, one million acres of Hageen Dura-1 had been harvested by hundreds of thousands of Sudanese farmers, and millions of Sudanese had been fed with grain produced by Hageen Dura-1.

Another drought-tolerant sorghum hybrid, NAD-1, was developed for conditions in Niger by Dr. Ejeta and one of his graduate students at Purdue University in 1992. This cultivar has had yields 4 or 5 times the national sorghum average.

Using some of the drought-tolerant germplasm from the hybrids in Niger and Sudan, Dr. Ejeta also developed elite sorghum inbred lines for the U.S. sorghum hybrid industry. He has released over 70 parental lines for the U.S. seed industry's use in commercial sorghum hybrids in both their domestic and international markets.

Defeating the Scourge of Striga

Dr. Ejeta's next breakthrough came in the 1990s, the culmination of his research to conquer the greatest biological impediment to food production in Africa - the deadly parasitic weed Striga, known commonly as witchweed, which devastates yields of crops including maize, rice, pearl millet, sugarcane, and sorghum, thus severely limiting food availability. A 2009 UN Environmental Programme report estimated that Striga plagues 40% of arable savannah land and over 100 million people in Africa.

Previous attempts by African sorghum farmers to control the deadly weed, including crop management techniques and application of herbicides, had failed until Dr. Ejeta and his Purdue colleague Dr. Larry Butler formulated a novel research paradigm for genetic control of this scourge. With financial support from the Rockefeller Foundation and USAID, they developed an approach integrating genetics, agronomy, and biochemistry that focused on unraveling the intricate relationships between the parasitic Striga and the host sorghum plant. Eventually, they identified genes for Striga resistance and transferred them into locally adapted sorghum varieties and improved sorghum cultivars. The new sorghum also possessed broad adaptation to different African ecological conditions and farming systems.

The dissemination of the new sorghum varieties in Striga-endemic African countries was initially facilitated in 1994 by Dr. Ejeta, working closely with World Vision International and Sasakawa2000. Those organizations coordinated a pilot program, with USAID funding, that distributed eight tons of seed to Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Mali, Mozambique, Niger, Rwanda, Senegal, Somalia, Sudan, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe. The yield increases from the improved Striga-resistant cultivars have been as much as four times the yield of local varieties, even in the severe drought areas.

In 2002-2003, Dr. Ejeta introduced an integrated Striga management (ISM) package, again through a pilot program funded by USAID, to deploy in Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Tanzania along with the Striga-resistant sorghum varieties he and his colleagues had developed at Purdue. This ISM package achieved further increased crop productivity through a synergistic combination of weed resistance in the host plant, soil-fertility enhancement, and water conservation.

By partnering with leaders and farmers across sub-Saharan Africa and educational institutions in the U.S. and abroad, Dr. Ejeta has personally trained and inspired a new generation of African agricultural scientists that is carrying forth his work.

Dr. Ejeta's scientific breakthroughs in breeding drought-tolerant and Striga-resistant sorghum have been combined with his persistent efforts to foster economic development and the empowerment of subsistence farmers through the creation of agricultural enterprises in rural Africa. He has led his colleagues in working with national and local authorities and nongovernmental agencies so that smallholder farmers and rural entrepreneurs can catalyze efforts to improve crop productivity, strengthen nutritional security, increase the value of agricultural products, and boost the profitability of agricultural enterprise - thus fostering profound impacts on lives and livelihoods on broader scale across the African continent.

Cosponsored By:

- College of Agriculture and Life Sciences

- College of Human Sciences

- College of Liberal Arts and Sciences

- Nutritional Sciences Council

- Office of the President

- World Affairs

- Committee on Lectures (funded by Student Government)

Stay for the entire event, including the brief question-and-answer session that follows the formal presentation. Most events run 75 minutes.

Sign-ins are after the event concludes. For lectures in the Memorial Union, go to the information desk in the Main Lounge. In other academic buildings, look for signage outside the auditorium.

Lecture Etiquette

- Stay for the entire lecture and the brief audience Q&A. If a student needs to leave early, he or she should sit near the back and exit discreetly.

- Do not bring food or uncovered drinks into the lecture.

- Check with Lectures staff before taking photographs or recording any portion of the event. There are often restrictions. Cell phones, tablets and laptops may be used to take notes or for class assignments.

- Keep questions or comments brief and concise to allow as many as possible.